Prof Penny D Sackett, Dr Albert Palazzo, Em Prof Ian Lowe, Prof Anne Poelina and Prof Quentin Grafton

26 August 2024

Climate disruption is the term used by scientists to communicate the magnitude and speed of the human-induced climate change now threatening the world. Of the six tipping points listed in a recent United Nations report on interconnected disaster risks, five are caused or exacerbated by climate change, namely: accelerated extinctions, groundwater depletion, melting mountain glaciers, unbearable heat, and an uninsurable future. This massive shock is already eroding Australian peace and security, and will continue to do so without an immense, immediate and sustained intervention to phase out fossil fuels. We need a new vision for our shared future.

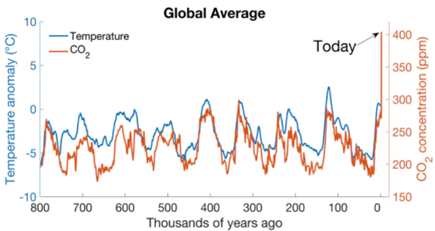

Earth – humanity’s space ship – has an onboard life support system that provides clean air, water, food, and climate control for all its inhabitants. This Earth System has varied slowly over the 100,000-year periods that separate ice ages, with accompanying oscillations in average Earth temperatures of about 5°C and sea level of many 10–100 metres. Vastly different ecosystems thrive during these stages; the conditions that humans associate with the rise of agriculture have only persisted for the last 12,000 years.

Yet in only 150 years, humans have damaged the Earth life support system so substantially that within the next five to ten years global average temperatures are virtually certain to soar above those seen at any time in the last 800,000 years, reaching 1.5°C above pre-industrial times. On current trends, by century’s end that temperature difference will double to a 3°C rise, which is 60% of the difference between an interglacial period and an ice age, but in the opposite direction into uncharted territory.

Global average temperature difference (blue) and atmospheric concentration of CO2 (orange) over the last 800,000 years. Low periods are ice ages, whilst high periods are interglacials; only about 5°C separates the two. Plot after Henley and Abram (2017).

Stoked by greenhouse gas emissions from fossil fuels for about 90% and by deforestation and destructive land use for the remainder, this enormous and rapid increase in the Earth’s surface energy content is altering local and global climate, rainfall patterns, storm characteristics, and atmospheric and ocean currents, with devastating consequences for ecosystems. Climate impacts are hitting harder and sooner than scientists previously expected. Many risks that 20 years ago were thought possible only after temperature increases of 3 to 4°C degrees are now thought likely at 1.5°C degrees above the pre-industrial normal.

Simply put, because climate is a fundamental element of Earth’s life support system, its disruption is an existential risk to the security of all Earth life, including humans. Furthermore, because climate disruption exacerbates other human security threats, it sits as a hub in the interconnected web of risks to Australians.

The devastating consequences of climate disruption are already evident in Australia, including unprecedented extremes across the country, with some areas of eastern Australia going from disastrous drought, heat and bushfires to equally disastrous rainfall and flooding in just a few years. The Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) noted that all areas of Australia are experiencing an increase in heat extremes with major impacts on natural systems, with some “experiencing or at risk of irreversible change.” The National Climate Risk Assessment identifies 56 climate risks to Australia, of which 11 were deemed in need of further in-depth study as a matter of high priority, namely risks to:

- Defence and national security

- National environment

- Health and social support

- Infrastructure and the built environment

- Regional, remote and First Nations communities’ well-being

- Primary industries and food

- Adaptation from unsuited and unresponsive governmental structures

- Community from legacy and future planning decisions

- Supply and service chains

- Economy

- Water Security

Little surprise, then, that the Australian Security Leaders Climate Group stated in March 2022 that “Climate change now represents the greatest threat to the future and security of Australians.” Direct impacts of global heating and climate extremes on health and wellbeing, and impacts on supply chains and world food prices could lead to social unrest and “increasing instability, conflict and forced migration from neighbouring nations,” they concluded, describing climate change as “an existential threat to nations and communities” across our region.

Climate disruption is a serious threat to food production systems because they are highly dependent on water resources and healthy ecosystems. Multiple regions already suffer from water cycle disruptions due to the rapidly changing climate. Heat and water stress on future global food production will result in deceasing yields even as water withdrawals increase. Australia is not immune. Risks to food and water security from climate disruption will contribute to mortality, morbidity and migration, with Australia particularly likely to experience inward migration. Our water resources have already been heavily damaged to due to climate disruption and mismanagement. As global heating continues, reversing this trend will require a new approach that places water justice at its centre.

Climate is linked to the digital revolution and artificial intelligence as well. Reducing energy consumption and conserving water resources are key to managing the causes and effects of climate disruption and ecosystem loss. Yet the digital revolution and the push to artificial intelligence are consuming these precious resources unchecked. Unexamined proliferation of artificial intelligence carries enormous risks to Australians, whilst voraciously consuming the resources fundamental to climate stabilisation and life on Earth.

The Great Barrier Reef (GBR) – the world’s largest coral reef ecosystem – is literally dying before our eyes. Its outlook is “very poor.” Mass bleaching events occurred in 1998 and 2002, and the five more following in rapid succession in 2016, 2017, 2020, 2022 and 2024, the last the worst to date. Temperatures may have already crossed a critical threshold. At 1.5°C of global heating, widespread mortality of warm-water coral reefs such as the GBR is very likely.

Health is central to human security. Climate disruption and the collapse of biodiversity is considered by global health professionals to be “the biggest global health threats of the 21st century.” Climate disruption is already compromising the health of Australians through extended heat waves, dangerous floods and storms, bushfire and bushfire smoke, increased mental and physical distress, and an increase in diseases spread by animals, all of which are causing human death and morbidity. Risks to human health rise dramatically with small increases in global temperature. Already peak heatwaves that occurred only once per 30 years in pre-industrial times in Australia can now be expected every 5 years. At global heating of 1.5°C, this frequency will nearly double to once every 2.7 years, and if heating of 3°C is reached, Australians will see such peak heatwaves nearly every year. With “just” 1.5°C of heating, thousands of global locations will experience what are now considered ‘once-in-100-years extreme-sea-level events’ at least once a year by 2100, with the tropics most affected. Yet climate disruption is yet to enter mainstream health planning in the country.

Climate disruption is hitting Australians in the pocket as well, not only through partial damage or complete loss of property due to climate extremes, but also in sharply rising insurance costs. The rise of insurance premiums, which are primarily a consequence of increased reinsurance costs, are continuing to outpace household income growth, and are being driven by the rising costs of climate disasters.

All this is cause for alarm, but an even greater worry is the risk of crossing tipping points in the Earth System, thresholds which if transgressed would lead to abrupt, far-reaching and effectively irreversible changes. Examples include permanent dieback of rain forests, changes in ocean circulation that would irreversibly affect local climate patterns, loss of ice that would sharply increase sea level rise, destruction of all the world’s coral reefs, and melting of permafrost that would dramatically accelerate global warming. A significant likelihood of crossing multiple climate tipping points exists above – the now inevitable – 1.5°C degrees of global heating, with increased risk every increment of warming thereafter.

The only way to substantial reduce the risk of these potentially catastrophic outcomes is to rapidly reduce the release of greenhouse gases. Current ambitions of Australia and most other nations are woefully inadequate; even if all the Paris Agreement unconditional national contributions were realised, the world would be expected to reach 2.9°C of global heating by the time today’s newborns are about 75 years old –– assuming tipping points are not crossed that would make matters worse In 2021, International Energy Agency constructed a range of scenarios of future energy use and consequent climate outcomes. The only one that held the increase in global temperature to 1.5°C degrees had no new fossil fuel projects from that date: no new coal mines, no new oil or gas fields, no coal-fired power stations that do not capture their emissions.

Given what is at stake, and the urgency with which action must be taken, it is clear that Australia’s current approach to fossil fuel development is irresponsible, as is that of many other nations.

Disruption of our life support system is the most urgent demonstration of our inappropriate engagement with the natural systems of this ancient continent. Earth-centred governance, drawing on the traditional knowledge and ancient wisdom of the First Australians could enable a new Australian Dream, committed to balance, co-existence, and peace with the whole of the natural world.